With the ‘Wagatha Christie’ preliminary poring over the annihilation of a big name friendship, four individuals share their encounters of foul play and injury.

As the defamation suit between Rebekah Vardy and Coleen Rooney thunders in the high court, the general population has heard many cases and counterclaims about Instagram stings, paparazzi ambushes and telephones lost in the ocean. However, one thing was obvious: one of the two ladies had been double-crossed. As Rooney claims, Vardy sold anecdotes about her kindred Wag to the Sun, or, as Vardy keeps up with, Rooney’s unjustifiable allegation has hauled her great name through the mud.

It is a muddled and corrupt story from which nobody – except for potentially the legal advisors – arises the better. Rooney has depicted Vardy’s WhatsApp trades about her as “evil”; Vardy has said that the dangers and misuse she got after Rooney’s allegations caused her to feel self-destructive. What is driving the previous friends to burn through millions broadcasting their most personal subtleties?

Double-crossing by a friend isn’t something you can simply ignore, says Dr Jennifer Freyd, a brain research teacher at the University of Oregon. “The very place where you ought to have the option to find support and insurance from the damages of life turns into the wellspring of mischief.” She instituted the expression “selling out injury” to depict the aggravation such bad form can cause. “We are a social animal varieties; when somebody betrays us, it’s a genuine danger to our prosperity.”

There are levels of double-crossing. For instance, the greater part of us will have encountered a friend meddling uncharitably behind our backs – or maybe we have been that friend. This is not Judas kissing Jesus in that frame of mind of Gethsemane. “In any case, what we find by and large is that selling out is harmful,” Freyd says. “Individuals who are sold out are probably going to have physical and emotional well-being difficulties.”

Annabel, who is in her 50s and lives in Wales, was deceived by her previous friend Jane. They met in the mid-2000s. Annabel maintained an expert business at a food market; Jane visited her stand frequently and befriended her on a promoting occasion. “We recently clicked,” says Annabel. “She was truly friendly. We’d go to one another’s homes for dinners.”

Annabel acquainted Jane with her friends and gave her work on her slow down, showing her all her business. Jane then, at that point, declared that she wanted to set up an adversary stand, selling similar items at a similar market. Annabel was shocked. “I told her that I was harmed and I figured it would be abnormal and unusual for others,” says Annabel. “It didn’t work actually and according to a business perspective we would have been sharing clients.”

Jane was unaffected, in any event, proposing that, assuming Annabel was troubled, she could jump at the chance to think about moving business sectors. Very much like that, their friendship was finished.

From the start, Jane’s stand didn’t influence Annabel’s deals too incredibly, yet after some time, her pay declined. “The market couldn’t support two comparative organizations,” she says. Ultimately, Annabel left. The experience caused her to feel “desolate “, like I could not trust anybody. I felt that individuals might very well be after what I had got.” She was, she expresses, “upset for quite a while”.

This is a typical reaction to sensations of selling out, says Holly Roberts, a psychotherapist with the relationship good cause Relate. “Whenever you open up to a friend, you make yourself defenceless against that individual,” she says. “That makes it hard. Since you’ve uncovered yourself sincerely to that individual and been wounded by them.” Roberts says these sentiments “can sit with you for quite a while”. Annabel has continued with her business. “I can be philosophical about it now,” she says. “Be that as it may, it positions pretty exceptionally in my set of experiences of agonizing individual encounters.”

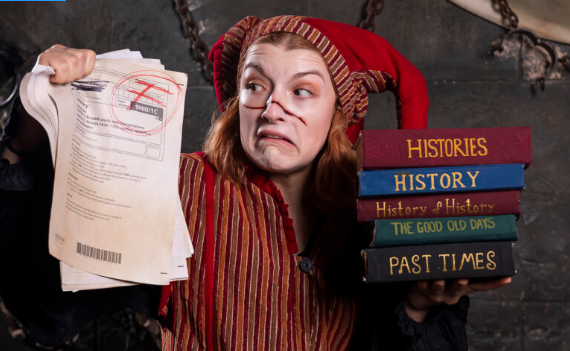

Disloyalty stories “are just about ancient”, notes Dr Lucy CMM Jackson, an associate works of art teacher at Durham University. Stories, for example, Euripides’ Medea, about a lady’s ridiculous mission for retribution after her significant other leaves her, “are so entrancing in light of the fact that they articulate a trepidation”, she says. “We recount selling out to figure out it, with the expectation that perhaps we can stay away from it or on the other hand, in the event that not, be more ready for it. At last, we return to the possibility of double-crossing so frequently on the grounds that we in all actuality do need to trust one another.”

According to Jackson, Medea “gets revenge since her name has been hauled through the residue”. Does she see matches with Vardy’s endeavour to reestablish her standing? “It’s all very frivolous,” she says. “I don’t get the feeling that such a praiseworthy lot has been surrendered in this cutting edge equal.”

Like Medea, Stacy Thunes’ account of disloyalty rotates around a beguiling sweetheart. Thus, a 61-year-old entertainer and screenwriter from London were deceived by her dear friend Billie in the mid-80s. Whenever Thunes became hopelessly enamoured with an attractive artist, she sorted out for the three to go for breakfast. At breakfast, regrettably, “his foot was really contacting hers under the table”.

That night, Thunes went to Billie’s loft. The lights were off, and Billie wasn’t noting the doorbell. Thus moved in through an open window. Billie rose out of her room. “I knew by the expression all over that he was there,” Thunes says.

She says that being sold out by Billie was more excruciating than being double-crossed by her boyfriend. “It caused me to feel like we were never truly friends,” says Thunes. “Like the friendship amounted to nothing. Such a long time of feeling that she had my back was gone in a moment.”

The people who are deceived frequently feel disgrace, says Roberts. “Individuals feel humiliated. They think: how is it that I could have freed myself up to this individual and allow them to do this to me? How is it that I could have been so gullible?”

Lisa, a handicap support specialist, realizes this feeling good. “I was unable to accept how dumb we’d been,” she moans. Lisa met Anna during the 1990s when they worked in contiguous shops in Edinburgh. “She was entertaining and kind and liberal,” says Lisa. “You knew where you remained with her. That’s what I loved.”

Whenever Lisa and her then-spouse moved to a little town on the east bank of Scotland, Anna followed with her young child before long. Surprisingly, Lisa assisted with childcare and went about as an underwriter on her investment property. “She was my family, and I was hers,” says Lisa. In any case, all that went to pieces when Anna’s landowner reached out. Anna had fallen behind on the lease.

Lisa proposed to loan her £1,500, the remainder of a little inheritance her granddad had left her. “She at first said no, however in the end concurred,” says Lisa. “I gave her the cash in real money. Also, that was the last time I at any point saw her.” Eventually, Lisa sorted out the story: Anna had utilized her cash to take off with a boyfriend. “I felt more irate at myself than at her, for being so innocent,” Lisa says.

Anna later composed a letter to Lisa, saying ‘sorry’ for harming her – however, not really for taking the cash. “She said it was my shortcoming since I constrained her to get it done,” says Lisa.

Not every person will finally accept the reality that accompanies a conciliatory sentiment, but weak. Cormac and Duncan met 10 years prior as educators at a similar school. They became friends rapidly, and Cormac acquainted Duncan with his social and expert circles. At the point when an administration post opened up, Cormac inquired as to whether he wanted to apply for it. “He said no,” Cormac says. “I would have had no issue if he’d said OK.”

Cormac went through weeks going over his meeting technique with Duncan. He was dazed to see Duncan there at his meeting in formal attire. “He’d gathered all the data from me and he’d involved me to lay the basis for getting to know everybody on the board,” says Cormac. Duncan landed the position. “I was in tears, since I realized I’d been managing somebody exceptionally cunning and manipulative and cautious, and it was wrecking.”

Duncan never apologized and spread bogus bits of gossip about Cormac around the school to make matters seriously enraging. “I needed to track down my own goal,” says Cormac. “I can’t allow him to live in my mind lease free. I told myself: ‘That is previously, and all that from now on will be great.'” Cormac wound up moving to an alternate school. “I needed to underscore it,” he says.

Selling out typically spells almost certain doom for a friendship. “That desire to pull out is a defensive reaction,” says Freyd. “You would rather not keep on being deceived. It’s undifferentiated from an instinctive reaction.” After Billie wrote to ask for pardoning, Thunes let her back into her life; however, she never confided in her in the future. “Each time I was with somebody, I realized she could have her eye on them,” says Thunes.

“assuming you’re both put resources into it, ” Modifying the relationship says Roberts is conceivable. “Check in with one another: how does this vibe? However, the trust may never return. Tolerating that can be a decent advance.” If you feel unfit to trust your friend, leave. “You don’t need to put yourself through it,” she says. “A few things can’t be fixed, and recognizing that is OK.”

Shockingly not many of the sold-out want to be hurt by their deceivers. They would prefer to relinquish the hurt and continue. “I was unable to allow it to make me frantic,” says Annabel. “I needed to continue doing my thing.” But every one of them is more cautious now, more conditional about who they let in, smarter about how they manage the trust that others place in them. “I’m helped to remember it every day, not because I need to cause myself to feel awful, but since I would rather not be that individual to hurt others,” says Thunes.

In any case, the demonstration of proceeding to trust in the wake of being harmed so seriously is a type of opposition in itself. They won’t quit associating with others because shutting off from the world allows their double-crossers to win. Lisa says she would loan Anna the cash again instantly, in any event, knowing all that she does now. “I’ve had such a lot of consideration displayed to me throughout the long term, as well,” she says. “That makes life wonderful.”