Paleontologists have found the most seasoned belly button known to science. It has a place with a Psittacosaurus, an individual from the horned dinosaurs Ceratopsia, in a fossil uncovered in China. The belly button doesn’t come from an umbilical line, as it does with vertebrates, yet from the yolk sac of the egg-laying animal, reports Science Alert’s Carly Cassella. Subtleties on the find were distributed for the current month in BMC Biology.

Current egg-hatchers like snakes and birds lose their belly button scar within a couple of days or weeks in the wake of bringing forth. However, different organic entities keep the “umbilical scar” until the end of their lives. While inside the egg, the undeveloped organism’s mid-region is associated with the yolk sac, which gives the incipient organism a food hotspot for developing and creating. The scar seems when the developing organism separates from the yolk sac and different films or as it hatches from its egg. The scar, known as an umbilical scar, is a non-mammalian belly button, says Gizmodo’s Jeanne Timmons. The Psittacosaurus umbilical scar is like that of a grown-up crocodile and is the main illustration of one in a non-avian dinosaur that originates before the Cenozoic period, a long time back, Science Alert reports.

Psittacosaurus was a bipedal dinosaur that lived during the start of the Cretaceous period. Fossils found in Mongolia and China of the horned dinosaur date from 100 million to a while back. Psittacosaurus was estimated very nearly 7 feet in length and was imperative for its high and restricted skull with a parrot-like snout. Paleontologists have likewise found a similar Psittacosaurus fossil, with a dinosaur cloaca and countershading cover, Gizmodo reports.

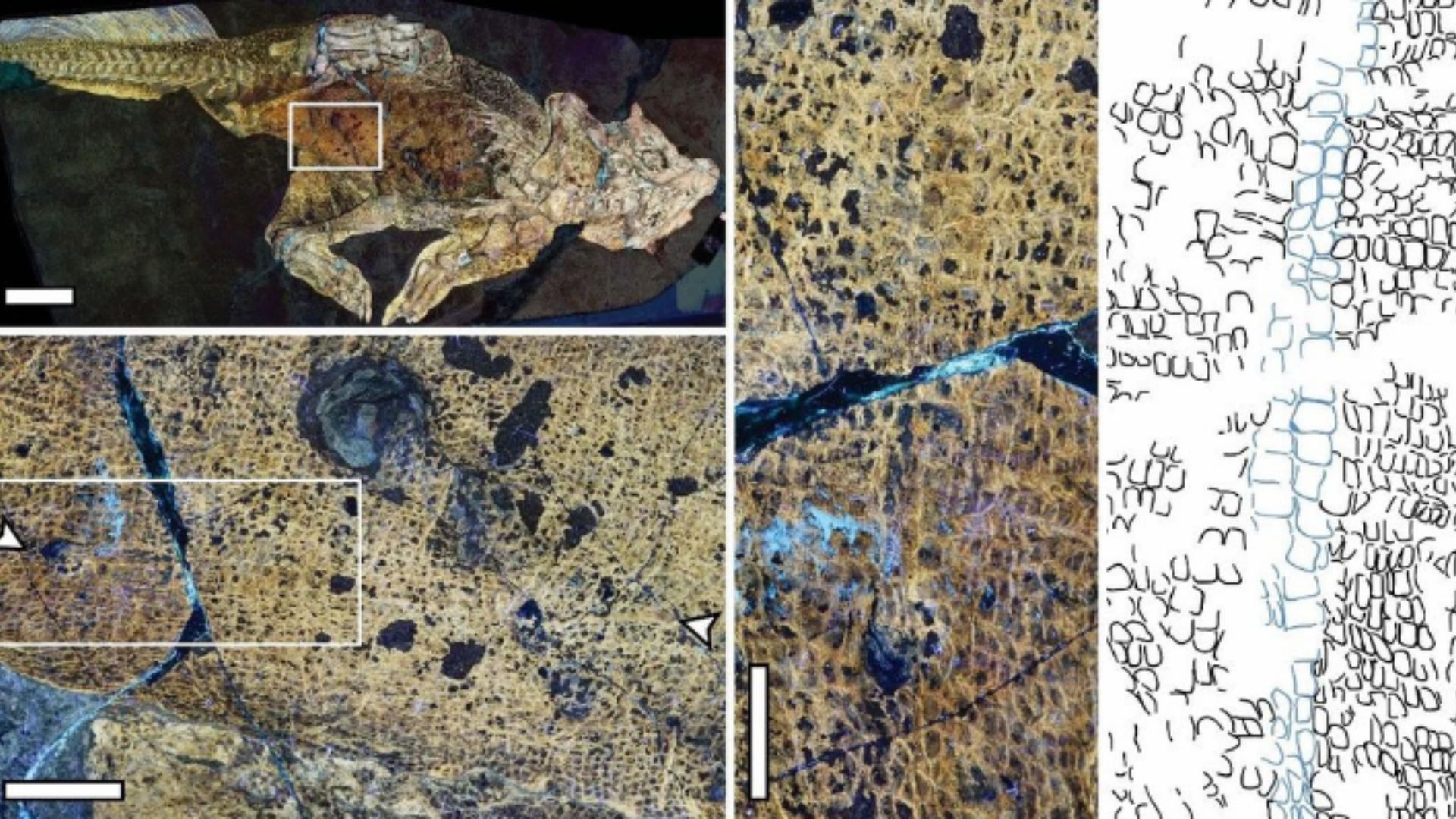

Specialists imaged the slippery belly button with Laser-Stimulated Fluorescence (LSF), an imaging procedure. They utilized a changed rendition of LSF, created to some extent by Michael Pittman, a vertebrae scientist at the University of Hong Kong and coauthor of the review with Thomas G. Kaye, a scientist at the Foundation for Scientific Advancement. The adjusted imaging strategy increments laser force in recently settled laser imaging methods without harming examples, permitting fine subtleties to be found in fossils that, in any case, would go concealed, Gizmodo reports.

The Psittacosaurus example with the belly button was uncovered in 2002 in China, tracked down lying on its back. Utilizing LSF, the group could investigate each scale, kink, and example scratched on the safeguarded fossil. “LSF draws out the detail in fantastic design,” Phil Bell, a dinosaur scientist engaged with the review, tells Gizmodo. “It truly looks like the creature could move up and leave. You can see every flaw and knock on the skin. It looks so new. Envisioning these creatures as no-nonsense elements, as opposed to simply dead skeletons, intrigues me. Rejuvenating them is one of the significant objectives of my work.”

The group had the option to picture the umbilical scar, which had blurred over the long haul, by seeing an adjustment of the example of skin and scales where the dino’s belly button would be. They likewise resolved that the scar was not from a mended physical issue because the umbilical scales were smooth and organized along the midline of the dinosaur. Assuming the scar was a physical issue, it would have shown regenerative tissue that could slice through and conflict with the scale design. To decide the age of the fossil, the group estimated the length and development of its femur and observed that the example was approaching sexual development at six to seven years of age, per Gizmodo.

Researchers had long guessed that egg-laying dinosaurs would have an umbilical scar, yet this study is quick to find proof of one, Science Alert reports. The scientists note that while a scar was found in this example, it might not have been available in all non-avian dinosaurs.